Part one: Lindow Man, the very Dark Ages and Mamucium

8 minute read

LINDOW Man was sacrificed almost 2,000 years ago. He’d been bludgeoned, garrotted and had his throat cut. His persecutors threw his body into a bog or pool which now forms part of the Lindow Moss area of Wilmslow, just south of the city. Celtic ritual murder such as this wasn’t unusual. Water carried religious significance for the Iron Age peoples in Northern Europe and it was common practice to make offerings of weapons, clothes, food and even each other, to the deities they imagined lived in water.

Lindow Man takes us back to a pre-Roman Britain, but generally the region has yielded little evidence of extensive human occupation in those early days. There have only been a few flints, axeheads and bits of pottery discovered in the area. What survives physically is found in the uplands, a modest hillfort in Mossley, a tiny stone circle above Bolton, but in prehistoric times Manchester was a fraction as active as, say, the ritual landscape of Wiltshire with its Stonehenge.

Close to Manchester United’s Old Trafford stadium is the A56, Chester Road, a Roman road. When the Roman surveyors planned that straight route in the years after 79AD they would have been cutting a road through a wilderness of scrub oak and birch where wolves, boar and bear roamed. A landscape under which rich coal seams lay waiting for the creative cataclysm of industry to happen 1,700 years later.

It amuses me sometimes to stand on the bridges over the Bridgewater Canal and the main Liverpool rail line close to White City Retail Park and take in the view across the city centre to the Pennines and imagine the almost virgin territory through which the Romans drove their straight paved line, eyeing up a good site for a fort.

It must have been the cohorts of XX Valeria Victrix legion, under General Agricola, who spotted Manchester's potential in 79 AD – a memorable year, especially for the citizens of Pompeii whose city was wiped out by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

The Romans recognised the strategic value of the rounded bluff over the confluence of the Rivers Irwell and Medlock and stayed for over three centuries. Their fort was garrisoned, at its peak, by an 800 strong mixed force of infantry and cavalry. This was an auxiliary regiment, not native Romans, but recruits or conscripts from the other provinces.

It’s during this time we have our first named Manc, adopted Manc. This was Lucius Senecianus Martius. He set up an altar here to the Goddess of Fortune. What did his eyes see, how did his brain interpret what he saw?

Martius was a soldier and primarily the place was military in character, but as often happened outside Roman forts a civilian settlement grew which accommodated the unofficial wives of the soldiers and attracted artisans and craftsmen, who set up furnaces and workshops.

During excavations in the 1970s a Christian 'magic square' dating from 175AD was found. This coded inscription spells the word Paternoster, the opening words of the Lord's Prayer in Latin. It’s the oldest evidence of Christianity in the country.

Seven roads met at the fort, more than at any other site in the North, one leads north east to Castleshaw Roman Fort, the vestigal remains of which can be seen below Standedge and above Delph in Saddleworth. Future movements of people and resources would, for convenience sake, move along these routes and come directly through Manchester. Roman authority officially abandoned Britain in 410 AD and eventually, the Saxons moved in.

Parts of the Roman fort have been reconstructed in Castlefield including the north gate and part of the west wall, along with foundation recreations of the granary buildings and some of the village structures outside the walls. A genuine stretch of wall remains hidden beneath a rail arch and is sadly inaccessible. Perhaps the main legacy of the Roman period comes with the name of the city complete with a delicious slice of hilarious nineteenth century reinterpretation..

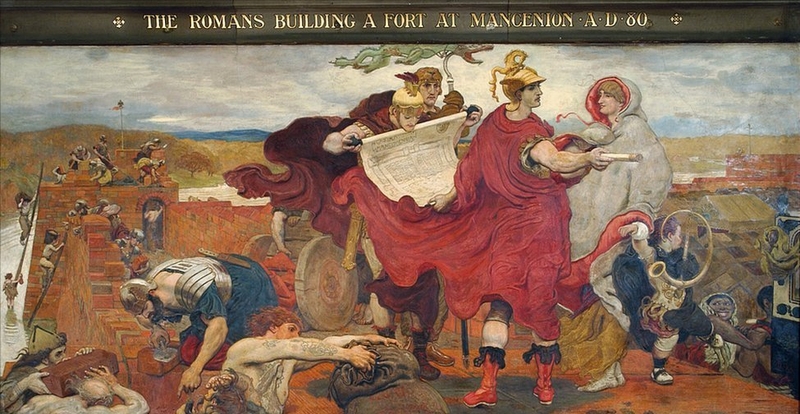

The Victorians thought Manchester’s Roman name was Mancenion and that’s how it appears in Ford Madox Brown’s Town Hall murals. Some Manchester men translated this fancifully as ‘city of men’. Modern scholarship now believes the name to have been Mamucium or ‘breast-shaped hill’ – a very different notion. Meanwhile, the Latin word 'castrum' meaning fort was twisted into the 'chester' element of the city’s name. Bravissimo, a lingerie retailer, once used the real Roman name in a promotional campaign.

We know almost as little about the Saxon period as we do about the area’s prehistory. We know they fished the rivers as boats carved from a single tree trunk have been discovered in the River Irwell. Still, the Dark Ages really were the dark ages in this region. The key physical development was the movement of the settlement centre of Manchester, at some point, from Castlefield a mile down the Roman Road to the area of, what is now, the Cathedral and Chetham’s. The rocky outcrop here, at the confluence of the Rivers Irwell and Irk was, in the lawless Dark Ages, easier to defend.

The Saxons also signed their names across the region. Greater Manchester is full of tons, hams, fords, hulmes. There is one physical remnant of the Saxon period. Straggling through the south of the city is the old boundary division of Nico Ditch.

Oh and there’s King Arthur as well. Of course, there is.

This is from The Annals of Manchester and Salford by William Axon from 1878. He quotes the seventeenth century writer Hollinworth. ‘It is sayd that a Sir Tarquine, a stout enemie of King Arthur, kept this castle, and neere to the ford in Medlock, hung a bason on a tree, on which bason whosoever did strike, Sir Tarquine, or some of his company, would come and fight with him, and that Sir Launcelot du Lake, a knight of King Arthur's Round Table, did beate uppon the bason, fought with Tarquine, killed him, possessed himselfe of the castle, and loosed the prisoners.’

But at this time Manchester, as with all Lancashire, suffered from its location, hemmed in by inhospitable marsh and bog to the south, isolated between the sea, the marshes of the Mersey and Irwell rivers and the hills of the Pennines. When the Domesday Book was compiled, after the Norman Conquest in 1066, Lancashire and Manchester warranted a mere one-and-a-half pages out of 1,700, and that as an appendix to Cheshire.

In the next chapter, we look at medieval Manchester. These histories are based on those in Jonathan Schofield’s Complete Guide to Manchester.

Read next: Myths of Manchester: Part Two

Read again: Campfield Market Halls, Castlefield, receives £17.5 levelling up boost

Get the latest news to your inbox

Get the latest food & drink news and exclusive offers by email by signing up to our mailing list. This is one of the ways that Confidentials remains free to our readers and by signing up you help support our high quality, impartial and knowledgable writers. Thank you!